Here's the Lizard as displayed by Starry Nights Pro - I like him better than the Hevelius lizard! (Yeah, I added the background color - wanted to see if he would change like a chameleon, but my magic wand seems broken 😉

My first excursion into the realm of the lizard I used Sissy Haas as my guide and once I had found the constellation, quickly checked out 8 Lacerae – very nice silver and pale blue – and 10 and 12 Lacertae, a bit more challenging and less impressive than 8. But it wasn’t until days later that I did some more checking and learned that several of the stars I thought were just line-of-sight companions to 8, really were part of it. In short, 8 turned out to be a very special find in a relatively obscure section of sky that’s easier to reach than you may think.

A few nights later with a gloomy forecast I still didn’t have a pursuit plan mapped out, however, and I went to bed real early figuring on reading when I got up in a few hours. (No I don’t sleep very long.) I was dead tired, having, among other things, evicted mice from my unused small observatory and cleaned up after them. (An operation had kept me out of the observatory for three months because I couldn’t lift the shutter or rotate the dome. Now, my strength recovered, I was ready to get back to using it.)

When I glanced out after a few hours sleep I was surprised to see Jupiter burning a hole in the haze to the east. Great – I needed to at least align the finder on the TV 101, so I would do that and maybe look at Jupiter a while. But instead I lined up the finder on Vega, got a really nice split of the double double (very steady skies) and then went searching for – and quickly found – Comet Garradd which had just recently paid a visit to the Coathanger. Hey – this was a much better night than the weather folks had predicted! Don’t you love it when that happens? So now I went for 8 Lacertae with the idea of finding all its components – and did so quickly with the 101. Then I noticed the 60/1000 Tasco sitting there on a shelf feeling ignored. I quickly swapped the 101 for the Tasco and enjoyed myself for better than two hours until the clouds closed in just as I was closing in on M34.

Lacerta may be totally unknown to you – as it was to me – but this is a three-for one sale – find one multiple star in Lacerta and you get the two others free of any extra effort.

Lacerta may be totally unknown to you – as it was to me – but this is a three-for one sale – find one multiple star in Lacerta and you get the two others free of any extra effort.

In fact, the one is a Sissy Haas “showcase” and Double Star Club double – that is both lists treat it as a double and that’s how we’ll treat it at first – but it’s really a quintuple that even in a 60mm scope makes a stunning triple. And nearby are two other doubles, 10 Lacertae and 12 Lacertae.

But enough! Let’s start with 8 Lacertae and how to find it, because I have to admit this is a general area of sky I’ve managed to pretty much ignore over the past half century or so. I’m lazy and where there aren’t bright guidepost stars I seldom venture. But I was feeling adventuresome on this night and besides, I wanted to find something John hadn’t gobbled up yet – something good. So I turned to the Lacerta section of the Haas book, and there were 8, 10 and 12 Lacerta, with 8 getting the coveted “showcase pair” designation. That was enough for me – lead me to the lizard! (Yeah, Lacerta is Latin for “lizard.” This isn’t one of those classic constellation, this is one that modern dude Johannes Hevelius dreamed up when he was creating his own sky charts in the late 1600s.)

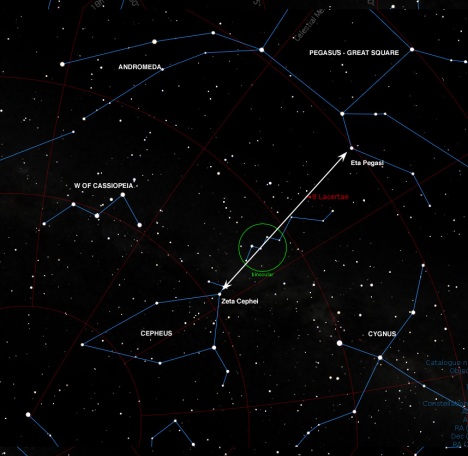

The trick, however is to find the lizard. So first you have to know the general area of sky to search. Here’s a chart that shows how Lacerta is bounded by better known – and brighter constellations. Though Cepheus is hardly bright – Cassiopeia, Andromeda, Pegasus (Great Square), and Cygnus are. If you are familiar with Cepheus you can draw a line from Zeta Cephei to Eta Pegasi and you’ll find the “Little Cassiopeia” W on that line – and continuing south you’ll find 8 Lacertae.

Finding Lacerta - click image for larger version of this chart. (Prepared from Starry Nights Pro screen shot.)

Starry Nights Pro does a connect-the-dots routine for Lacerta that looks like this – sort of a lightning bolt.

That may look easy enough to find once you know the general area of sky to look in – but nearly all those stars are either at the weak end of magnitude four, or the strong end of magnitude five. So – if your eyes are well dark adapted and your skies dark enough so you can see all seven stars in the Little Dipper, you should be able to detect these with your naked eye. While I can just do that in my skies, I still found it confusing, so I took an easier route. I used low power binoculars with a 7-degree field. Here’s what that gives me when looking at just the northern portion – essentially a little version of Cassiopeia’s well-known “W” asterism.

That may look easy enough to find once you know the general area of sky to look in – but nearly all those stars are either at the weak end of magnitude four, or the strong end of magnitude five. So – if your eyes are well dark adapted and your skies dark enough so you can see all seven stars in the Little Dipper, you should be able to detect these with your naked eye. While I can just do that in my skies, I still found it confusing, so I took an easier route. I used low power binoculars with a 7-degree field. Here’s what that gives me when looking at just the northern portion – essentially a little version of Cassiopeia’s well-known “W” asterism.

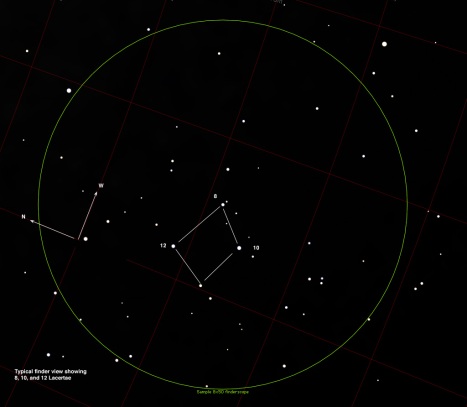

If you are comfortable you’ve found Lacerta, then finding 8 Lacertae should be easy with either binoculars or finder. You get “Little Cass” in your field and move south about one field of view. Here’s what you should see. That little diamond is a bit irregular – a diamond in the rough – but I find it shows up well in small binoculars or finder and is my key for locating not only 8, but 10 and 12 Lacertae as well.

But the one you want to start with is 8 Lacertae because it is so easy to split, even with a 60mm scope, and once you’ve found it, it will be much easier to identify the others. What’s more, while 8 Lacertae is a wonderful double in any scope – a real gem – it is a very nice triple in a 60mm and in a 100 mm or larger it becomes a quintuple. In fact, if you are careful about your identification, you’ll see a quadruple with a 60mm. The problem is that last star is far out and easily confused with other stars in the same field.

For me this also proved to be a reintroduction to the sharpness of a Tasco 60mm F16.6. What a lovely scope for doubles! And mounted on a T-Mount (a short, sturdy parallelogram mount made by Universal Astronomics) it was absurdly comfortable to use even though 8 Lacertae was very near the zenith at the time of observing. And truth is, the diamond I speak of was best revealed in the 6X30 finder on that scope. (A larger finder showed more stars and that tended to obscure the pattern.)

For the Double Star Club all you need to find is 8 and split it as double. Here’s the Club’s listing.

| 8 Lacerta | 22h 35m.9 | +39° 38′ | 5.7, 6.5 | 22.4″ | 186° |

But even if you’re using a 60mm, don’t cheat yourself by not looking for more. Just take your time, pay real close attention to position angle, split, and magnitude of the various components.

8 Lacertae

RA: 22h 36m Dec: +39°38′

Mag: AB 5.7, 6.5; AC 5.7, 10.5; AD 5.7, 9.4; AE 5.7, 7.2

Sep: AB 22.2″; AC 48.6″; AD 81.7″; AE 336.6″

PA: AB 185°; AC 158°; AD 81.7°; AE 239°

Spectral type: A – B2Ve , B – B2V, C – ?. D – A0, E – F0

Whew! That’s a lot of numbers, but take them one at a time. First, the AB split is wide and there’s less than a magnitude difference, so this is simple, Just sit back and enjoy – but also note that the PA is 185° and since that’s nearly due South it gives you a good idea as to the direction of the remaining, more difficult stars.

Whew! That’s a lot of numbers, but take them one at a time. First, the AB split is wide and there’s less than a magnitude difference, so this is simple, Just sit back and enjoy – but also note that the PA is 185° and since that’s nearly due South it gives you a good idea as to the direction of the remaining, more difficult stars.

AD was easy for me to spot next for two reasons – first, the separation is almost four times that of the AB pair, and second it’s a full magnitude brighter than the C component. And if you take AB as an indicator of south, than AD is roughly east at PA 81.7°.

Those three then fit together to make a reasonably compact triple when viewed at 90X in the 60mm. But with the 60mm I really couldn’t find the C component. It was too close to the brighter stars and at magnitude 10.5 is the dimmest of the group. The separation and PA tell you it’s roughly halfway between B and D in the south southeast area. I already had a pretty good idea where it was because I had seen it reasonably easily with the 4-inch. But honestly, I wasn’t sure I was detecting it with the 60mm, though I got a hint of it from time to time.

The E component is difficult only because it’s so far off and can be confused with other stars in the field that are apparently not members of 8 Lacertae. Once again, though,the numbers come to your rescue. First, the PA is 239° – that’s darned close to southwest and since AB indicates south you should have an easy time knowing which direction to look. What’s more, at 7.2 E is quite bright and it’s a whopping four times as far away as D.

That still means it should be well within your field of view. For example, if I were using a 10mm Plossl (100X) on my 60mm Tasco, I’d have a 30 minute field of view. Put AB in the center of that field and E would be about 6 minutes away – a bit less than half the distance to the edge of my field of view. So I would be looking for a fairly bright companion (7.2) to the southwest of the primary, and a bit less than halfway to the edge of the field. (Of course your field of view will vary with the scope and eyepiece, but you get the idea. )

Aesthetically E doesn’t do much for me – but it’s nice to have to round out the picture.

Moving on to 10 and 12

To find, review the chart showing the diamond – 10 and 12 are identified on it, as well as 8. I’ll repeat the chart here.

What about 10 and 12 Lacertae? Frankly, they don’t excite me all that much, but I like the fact that they occupy a couple of the other points on the diamond and heck, if 8 Lacertae has brought you to the neighborhood, go ahead and split them!

For me these were targets already found on my first night using the CR-6 refractor. I didn’t feel inclined to pursue them with the 60mm, though I probably will another night. Though their companions are 10th magnitude, the separation is very wide – about twice that of the familiar blue and gold Albireo.

10 Lacertae

RA: 22h 39m Dec: +39°03′

Mag: 4.8, 10.3

Sep: 62.2″

PA: 49°

Spectral type: O9V

I found the primary white, the secondary a faint blue dot nearby. Yesm judging by it’s spectrum you should see some blue in the primary. I didn’t.

12 Lacertae

RA: 22h 41.5m Dec: +40°14′

Mag: 5.2, 10.8

Sep: 69.1″

PA: 15°

Spectral type: B2III

This pair is about half a magnitude fainter than 10 Lacertae, but the PA puts the secondary in the same quadrant and it’s about the same distance, so if you can split 10, you should be able to split 12 – unless, of course, 10 was right on the edge of what you could do.

Filed under: DSC-60 Project, Lacerta, Uncategorized | Tagged: 10 Lacertae, 12 Lacertae, 8 Lacertae, DCX 60, Double Star Club, Lacerta, Lizard, quintuple | Leave a comment »