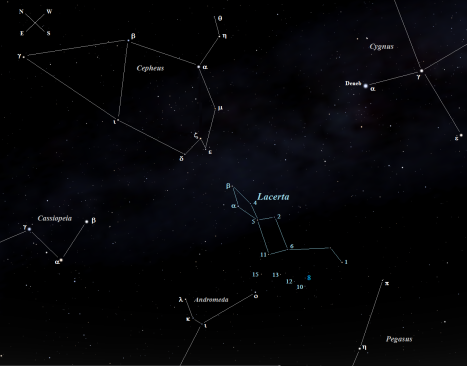

More than once I’ve stumbled across a multiple star with so many components I’ve wondered if all of them will fit in the field of view of a wide angle eyepiece. Two questions always bounce from one side of my starlit cranial compartment to the other: Why, and How? As in Why so many components, and How did they come to be added to the few original components (usually two)?

KR 60 — named for Adalbert Krueger (1823-1896), a German astronomer who in 1873 was conducting observations for the Astronomische Gesellschaft Catalog — is one such star. The multitude of components generates so much data that a spreadsheet is required to contain it all. Closer scrutiny shows a total of twenty individual components with four different prefixes, and there easily could have been five if credit had been given where credit was due (more on that later).

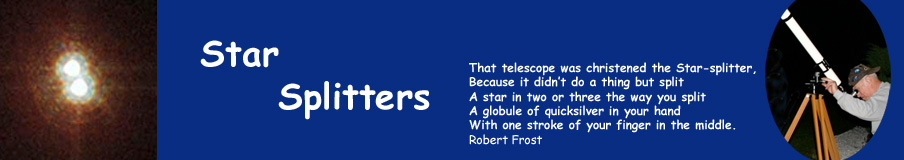

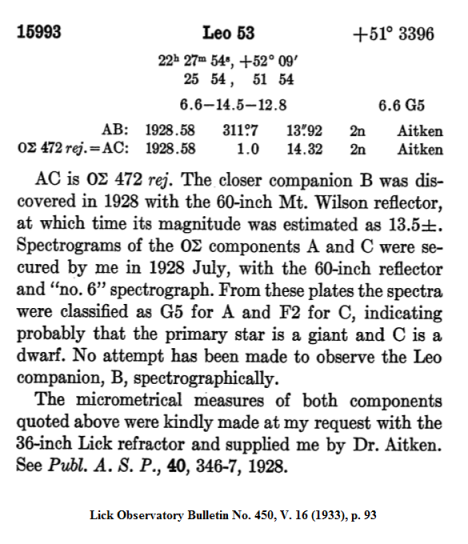

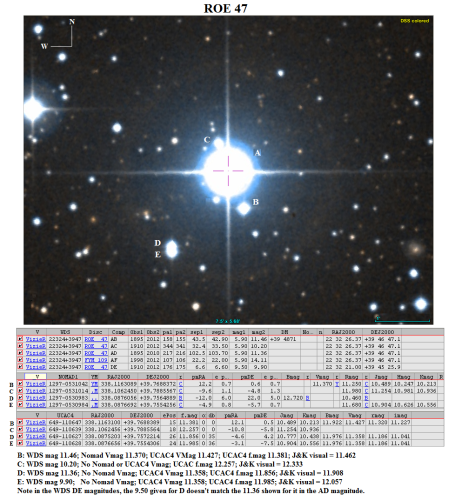

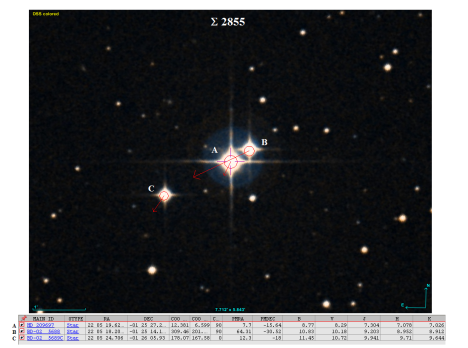

List of components for KR 60 (from the Stelledoppie web site). Click to enlarge.

Another characteristic that jumps out fairly quickly as you scan through the list of components is all but three of them are fainter than 13th magnitude (or four, if you import the 13.02 magnitude “H” component into the brighter grouping). Which raises another question of stellar magnitude: why include all those fourteenth and fifteenth magnitude components?

And buried within all the double star data, multiple identifications, and eye-straining magnitudes is a tale that involves quite a few more observers than the four who are connected to the KR, HEL, HZE, and FYM prefixes. Those observers include some of the most astronomically famous names of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: S. W. Burnham, Eric Doolittle, and E.E. Barnard.

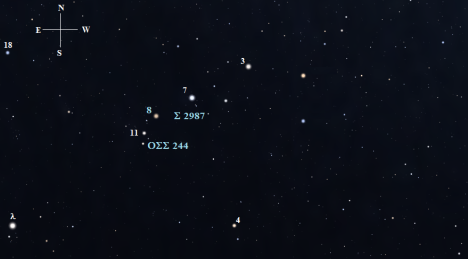

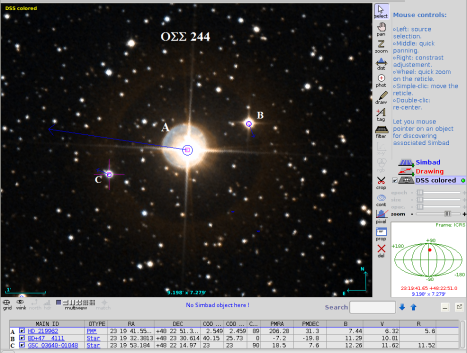

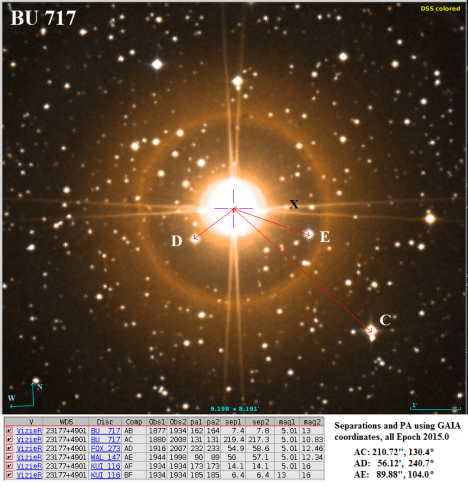

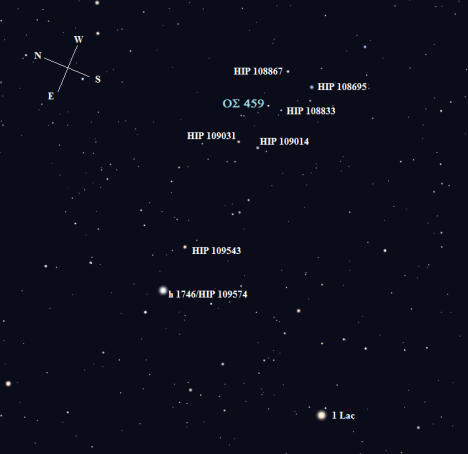

Prior to delving into the depths of the details, let’s take a look at an Aladin image of KR 60 with all of the components labeled:

Aladin image with labels added. “K” is buried in the glare of the AB pair, and “S” can barely be seen protruding from the west side of AB. North is up, east is at the left. Click to enlarge.

After your eyes overcome their attraction to the bright triangle created by the AB, C, and I members of this tribe, you begin to notice there are numerous faint stars in the surrounding area that have not been designated as components — or at least not yet, anyway. And that gets us back to a question implied in the first paragraph above: what was the logic for including some of the faint components and ignoring others?

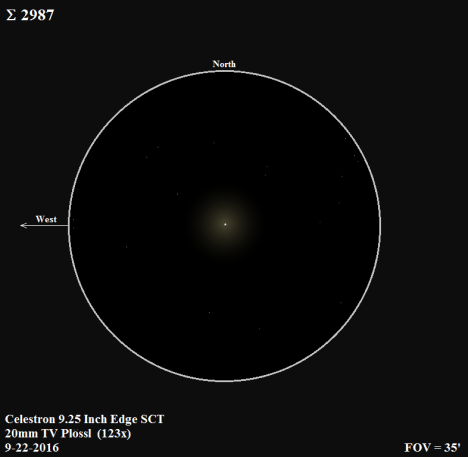

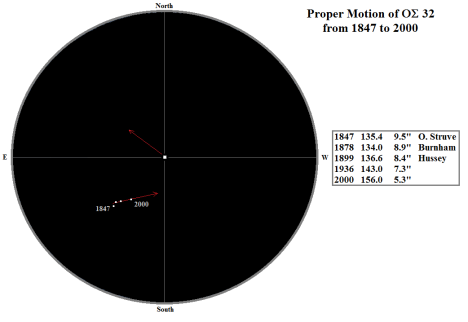

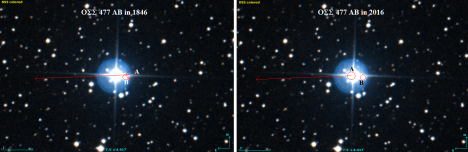

Before we start down that road, we need to look at two important details that influenced everything which occurred after Krueger’s initial 1873 observation of KR 60. The first is the distance of the primary, which the most recent Simbad and WDS data places at 13.05 light years. Normally when a star is that close to our planet, it displays a significant amount of motion relative to the Earth, otherwise known as proper motion. Not surprisingly, that’s what we see with the binary AB pair of KR 60. The rate of motion relative to our position in the solar system is almost a full arc second a year, which is fast — not fast enough to propel the AB pair to first place in the speed department among its stellar competitors, but fast enough for its motion to be obvious in relation to the many background stars surrounding it. The specific proper motion numbers are guaranteed to catch the eye of those who spend time looking at this kind of data. The WDS numbers are -806 -399 for the A component, which translated into a less arcane form means the A component is moving at the rate of .806 arc seconds per year west and .399 arc seconds a year south. Visually, those numbers look like this:

Notice that KR 60 AB and “C” have been shifted to the upper left of this image in order to allow room for the entire length of the proper motion vectors of the AB pair to be shown, which are the red arrows pointing to the southwest from AB. The red arrow emanating from the star between the “I” and “G” components is UCAC 739-08128 (also labeled LSPM J2228+5739), which is a high proper motion star that is not part of the KR 60 system. (Aladin image showing Simbad’s proper motion vectors, click to enlarge).

A fact I’ve skipped over up to this point is that “A” and “B” are an orbital pair, with an orbital period of 44.67 years per the data in the WDS (scroll down at this link to see the data and orbital diagram). Consequently, the proper motion of the “B” component is essentially the same as the parent “A” component, although the WDS data for “B” (-713 -321) shows a slight variation from “A”, which is also visible in the divergence of the two arrows above. The reason for that is the orbital motion of “B” imparts a slightly different motion to it as it circles the “A” component.

Now that we have the preliminaries pretty well covered, let’s get back to the history of the multiplicity of components. The best place to start is with the first component discovered, which normally would be the “B” component of the AB pairing — except in this case it’s not. If you scan down the column labeled “First” in the spreadsheet-like chart below the second paragraph above (“First” refers to the first date of measure, “Last” to the last date of measure), or click on this link to see it in a separate window, you’ll discover the “I” component was the first to be added. According to the dates listed, “I” was discovered in 1873, which means it preceded “B” (as well as “C”) by seventeen years (1873 versus 1890). Except it didn’t and it wasn’t — wasn’t discovered in 1873 and didn’t precede “B”. If you’re dazed and confused at this point, you’re not the first.

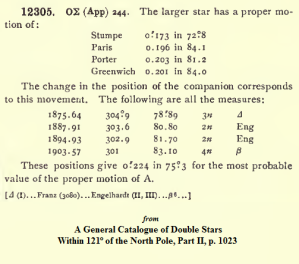

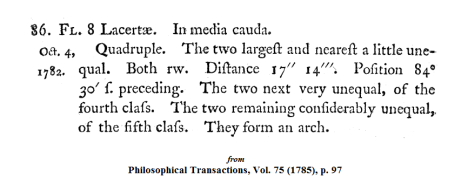

It’s amazing what surprises lie dormant in the dust of old records, waiting for some unsuspecting person to trip over them while on the way to somewhere else. In this case, that person was me, and what I stumbled over was a very odd comment on page 987 of the second volume of S.W. Burnham’s 1906 General Catalog of Double Stars within 121° of the North Pole: “Noted by Krueger in A.G. Hels., ‘dupl. 12″ pr. Com. 9.3‘ in 1873.73.” I had to dig out my data digging shovel to find out what that reference meant, but eventually I discovered an explanation by Burnham on p. vii of the second volume of the 1906 catalog: “Stars noted as double by Krueger in A.G. Helsingsfors-Gotha. The first measures of these pairs are found in Publications of Lick Observatory, Vol. II.”

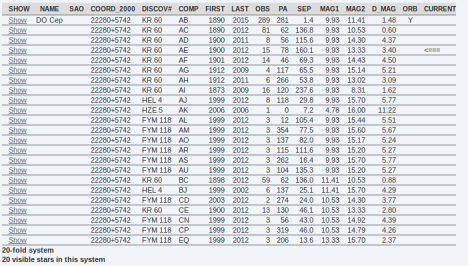

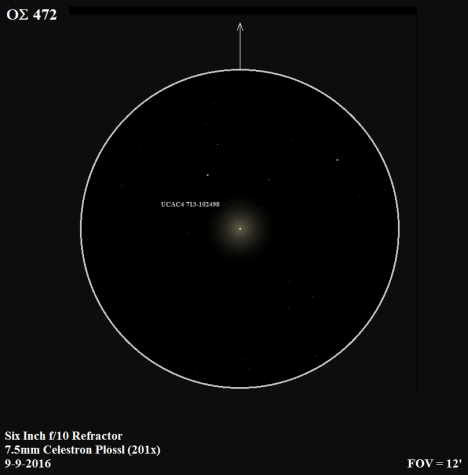

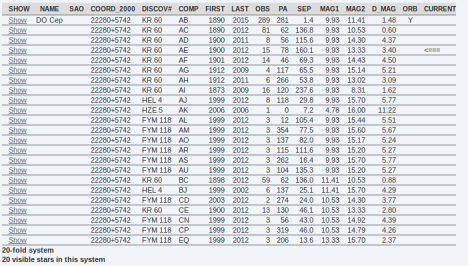

KR 60 is on the top line — note that Burnham used a “K” for Krueger at the top of the left hand column, as opposed to the KR currently used in the WDS. Click to enlarge.

With the aid of Google Books, I tracked down the Lick volume and found a table Burnham had compiled which consisted of stars Kruger had designated as double. In the excerpt at the right from that table the pair which Burnham labeled as “K 60” is at the top of the list, and in the right hand column Burnham added the notes which Kruger “appended concerning such of the stars as appeared double.” (p. 147 of source of the Lick volume).

That note refers to the magnitude of the secondary (9.3), which is identified by the term “Com.”, an abbreviation for comes, which was a term used in the early to mid-nineteenth century (possibly from Latin, although I can’t pin that down) for the secondary of a double star (it had pretty much fallen out of use when Krueger made his observation in 1873). Also shown is the separation (12″) and the magnitude of the primary (9.1).

Burnham’s 1890 KR 60 AB and AC measures are at the bottom of this list. Click to enlarge.

On page 150 of the Lick volume, Burnham lists his 1890.79 measures of the AB and AC pairs of KR 60, which are shown at the right (K 60, at the bottom of the excerpted page). Notice that neither of Burnham’s measures are anywhere near the 12″ separation referred to by Krueger (the column labeled “D” lists the separations, or distances, measured by him). And that 12″ separation referred to by Krueger is nowhere near the 195.4″ separation the WDS shows for the 1873 measure of the “I” component. So what star exactly was Krueger referring to in his 1873 catalog?

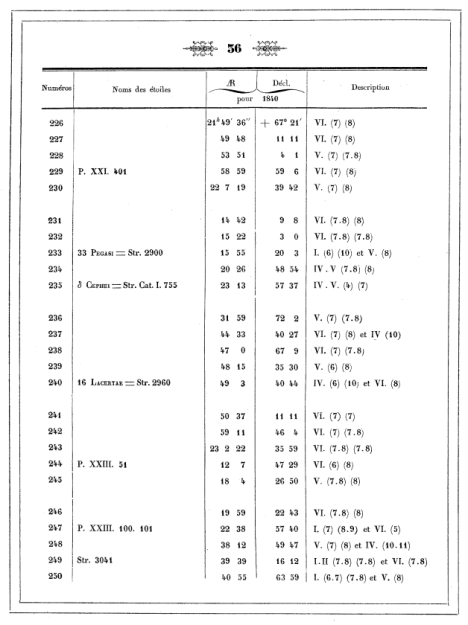

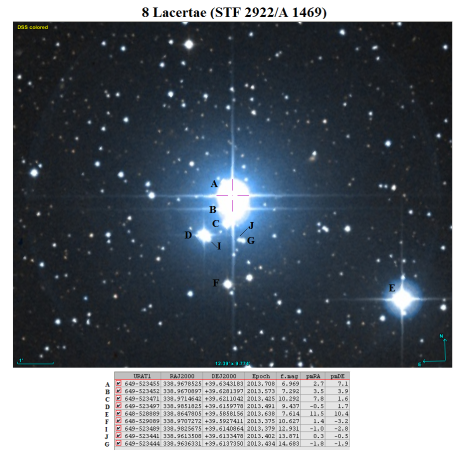

The only thing to do at this point was to see if I could track down the publication with Krueger’s 1873 observations. After a bit of internet excavation, I found what I was looking for in Google Books, adorned with a formidable title: Catalog von 14680 Sternen zwischen 54° 55′ und 65° 10′ Nördlicher Declination 1855 für das Aequinoctium 1875 nach Beobachtungen am Achtfüssigen Reichenbach’schen Passagen-Instrument der Helsingforser Sternwarte auf der Sternwarte der Universität Helsingfors in den Jahren 1869 bis 1876 und auf der Herzoglichen Sternwarte zu Gotha in den Jahren 1877 bis 1880 von A. Krueger. It’s actually the fourth volume of the 1890 Astronomische Gesellschaft Catalog, which covers the area of sky between 55 and 65 degrees of declination.

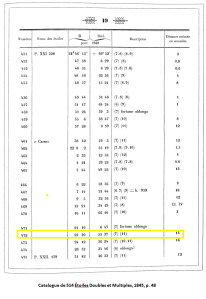

The key to unlocking Krueger’s cryptic comments! Click to enlarge.

That publication is a list of individual stars sorted by right ascension — in other words, it’s not a double star catalog. Each listing includes Krueger’s catalog number, the magnitude of the star (Gr.), and of utmost importance for resolving this puzzle, the Bonner Durchmusterung catalog number (also referred to as DM in the WDS) in the right hand column. Because this isn’t a double star catalog, there are no columns for separation and position angle. However, Burnham was thoughtful enough to include Krueger’s catalog number for the “A” component in his listing of KR 60, which is 13170. And since both KR 60 A and KR 60 I have Bonner Durchmusterung catalog (BD) numbers assigned to them, it was easy to locate them in the right hand column of Krueger’s catalog and cross-reference them to his catalog numbers in the first column. The BD number for the “A” component is +56 2783 (Simbad incorrectly assigns the number to the “C” component), which corresponds to Krueger’s catalog number 13170, and the BD number for the “I” component is +56 2784, which corresponds to Krueger’s catalog number 13177. And in fact if you look closely at Krueger’s entry for 13170, the 9.1 magnitude “A” component is adorned with a superscripted “3”, which refers to a foot note that appears at the bottom of that same page — and that footnote reads “Dupl 12” praec.; Com. 9m.3”. Which is the source of Burnham’s cryptic note that started my meandering path through the dusty stellar archives.

The BD number cited here by Burnham refers to what is now cataloged as the “I” component of KR 60. Click to enlarge.

Also included in Kruger’s catalog listing are the coordinates for each star, so having identified which of his catalog numbers are the “A” and “I” components, it was possible to plug the coordinates for the two stars into a spreadsheet and calculate the separation and position angle of the AI pair at the time he recorded his data. The result was a separation of 195.311″ and a position angle of 151.9°. The first data listed in the WDS for the AI pair (dated 1873) is 195.35″ and 151.9°. So now we know where the 1873 WDS data for the AI pair came from. In fact, those WDS numbers match the measures listed by Burnham on p. 988 of his 1906 catalog, where he also refers to what we know as the “I” component by it’s DM number (shown above at the left). Burnham didn’t add this star to his catalog, or designate it with a letter, which would indicate the letter designation came after several of the other components were added to the KR 60 system in 1900 and 1912. At this point, it was puzzling what would prompt the addition of the “I” component to the KR 60 conglomeration given its distance from the primary and the fact that it’s 1.6 magnitudes brighter than the primary.

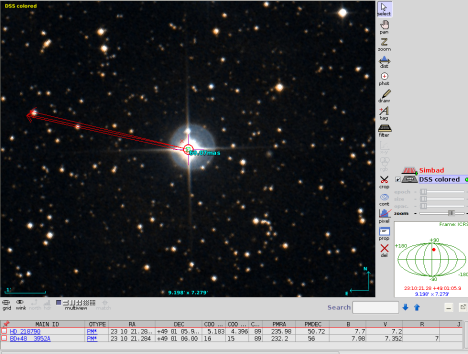

But what about that 12″ separation referred to by Kruger in his observing notes? Given the rather high rate of proper motion of the AB pair, the obvious thing to do at this point was to load the Simbad database into Aladin and use the epoch slider tool to see where the AB pair was in 1873 in relation to the surrounding stars. That bit of pixelated sleight of hand resulted in the AB pair being positioned very close to the the “C” component. Using Aladin’s measuring tool, I measured the 1873 distance of AB from “C” at 12″ with a position angle of 46°.

There’s a barely visible red dot southwest of the “C” component which is visible at the end of the yellow arrow. That dot marks the location of the AB pair in 1873. Click to enlarge.

Closer look at the conjunction of the AB and “C” components seen at the center of the larger image. Click to enlarge.

As you can see in the image above, there’s a pair of blue circles superimposed on the AB pair, which dates the image to 1992. When the epoch slider is moved to 1873, it projects the blue circle backward in time, which in this case means AB is projected northeast towards the “C” companion — or in other words, in the reverse direction of the blue proper motion lines radiating to the southwest from AB. A closer look at the 1873 positions of of AB and “C” is shown above at the right. In that view you can see a short arrow projecting a very minor amount of proper motion for “C” towards the southeast (the WDS proper motion data for “C” is very minimal, +003 -001, meaning its virtually stationary relative to the AB pair). A bit of additional research found Eric Doolittle had arrived at similar 1873 measures in a 1900 paper in the Astronomical Journal. I stumbled across his numbers buried in this footnote to a discussion of his measures of the AC pair: “The motion here derived would give for the position of the companion in 1873.7: 41.0°, 11.76″.”

So after a long and unplanned detour away from what aroused my initial curiosity, it turns out the “I” component was not in fact measured by Kruger in 1873 or even considered as a companion to the primary of KR 60. Instead, we’ve discovered the original historical secondary of KR 60 was the “C” component, not the “I” component, and certainly not the “B” component, which was discovered and added in 1890 by S.W. Burnham. From this point, uncovering answers to my original question about the reason for all the other components was rather straight forward.

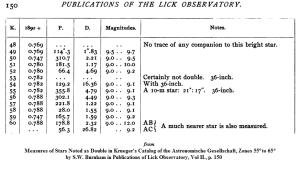

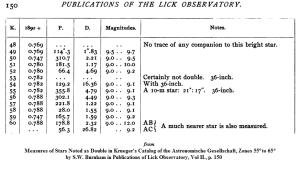

S.W. Burnham’s plot of the orbit of the AB pair, as well as their proper motion. Click to enlarge

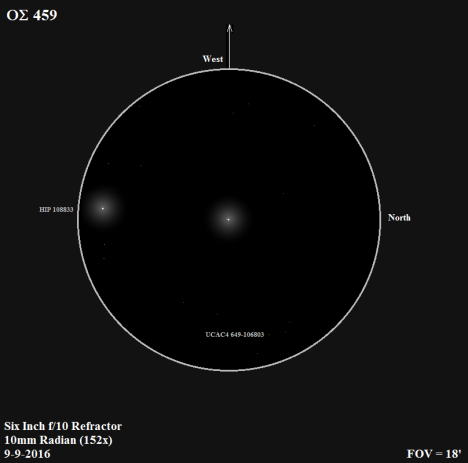

Burnham not only discovered the “B” component of KR 60 in 1890, but also quickly realized that “B” was orbiting “A”. Shown at the right is his 1906 plot of the orbital motion of the pair based on his and other observers’ measures between 1890 and 1906. He also was the first person to provide a careful measure of the AC pair that included the position angle as well as the separation (also in 1890). Also shown at the lower left of the diagram is his plot of the proper motion of the AB pair, which he based on its motion relative to “C”.

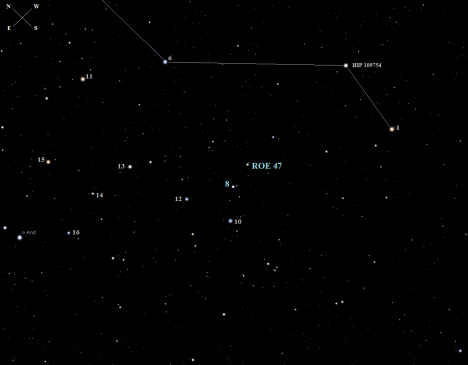

The rapid proper motion of the AB pair was also noticed by Eric Doolittle, who combined his own 1898 and 1900 measures with those of Burnham to arrive at a rate of proper motion of .093″ per year in the direction of 247.9 degrees (source). One of the stars he used as a reference point in order to make those determinations was the one now cataloged as the “I” component of KR 60, which he identified with Krueger’s catalog number of 13177.

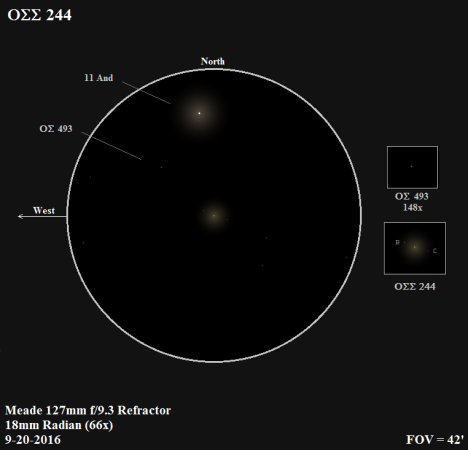

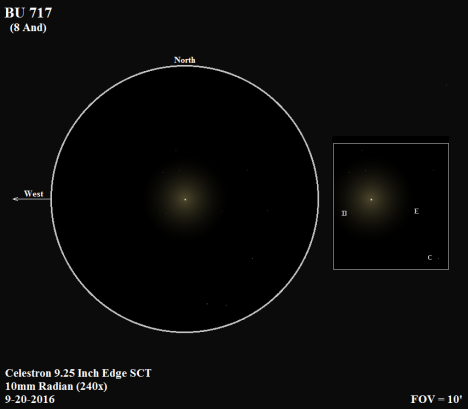

Doolittle’s work caught the attention of E.E. Barnard, who responded in the Astronomical Journal just two issues after Doolittle’s article with measures of two stars which he labeled as the “D” and “E” components. He added the two additional components because of the high rate of proper motion of the AB pair, stating “I have therefore made a series of measures with the 40-inch, introducing two other smaller stars to more thoroughly explain the character of the motion.” Barnard also suggested designating the AB pair as β 1291 since the “B” component was discovered by Burnham, not Krueger. However by that time, β 1291 had already been used to designate a pair of stars in Andromeda (WDS 00352+3750), so apparently the idea was dropped. But Barnard was correct — the AB pair should be designated with a BU in order to credit Burnham with the discovery of “B”.

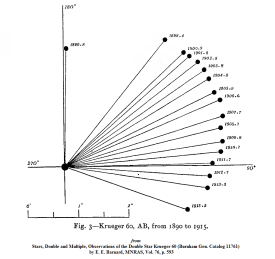

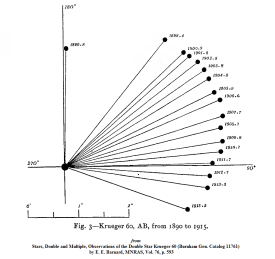

E.E. Barnard’s plot of the orbital motion of the AB pair. Click to enlarge.

In 1903 Barnard published another paper in the Astronomical Journal which introduced measures for an additional star, which he designated as the “F” component. He explained the addition of the new component as useful in determining the motion of “B” was orbital, as opposed to rectilinear (straight line motion). He also used the star later designated as the “I” component as a reference point of measure, referring to it by Krueger’s catalog number, 13177.

Still entranced by both the orbital and the proper motion of KR 60 AB, Barnard in 1916 published a lengthy paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in which he introduced his 1912 measures of two more stars, designated by him as the “G” and “H” components of KR 60. He also published measures for several additional stars in the vicinity of the AB pair, to which he didn’t assign component labels.

So by 1916, with Barnard having added components to KR 60 up to the letter “H”, I had a hunch the so far unlabeled “I” component would show up in the next large double star catalog published, which was R.G. Aitken‘s 1932 New General Catalogue of Double Stars Within 120° of the North Pole. I found it on pages 1385 and 1386 of the second volume, and discovered Aitken had only listed Burnham’s 1906 and 1910 measures. No mention was made of the measures Burnham had derived from Krueger’s 1873 coordinates for “A” and “I”.

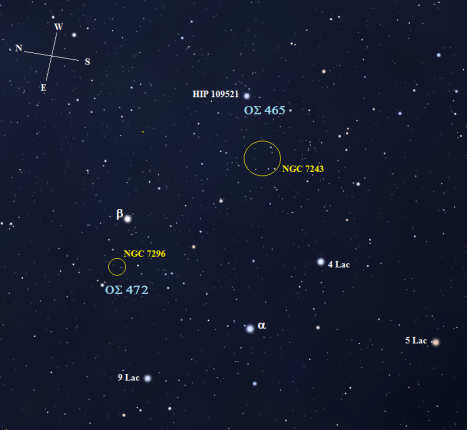

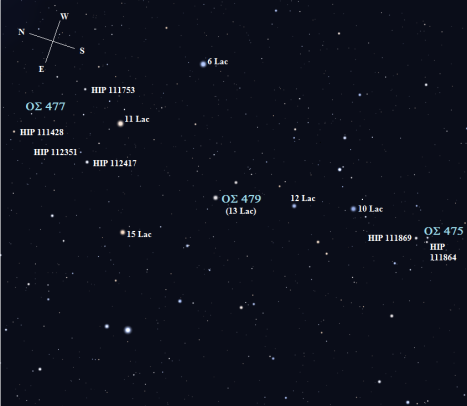

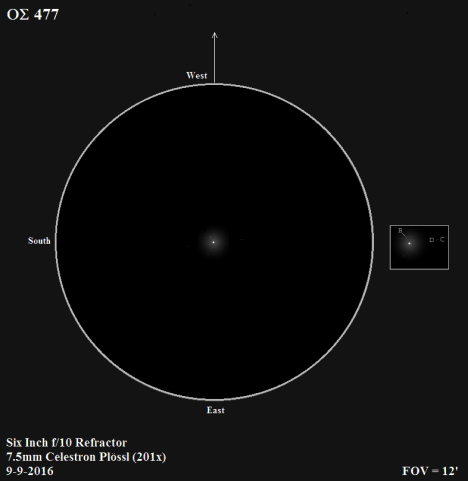

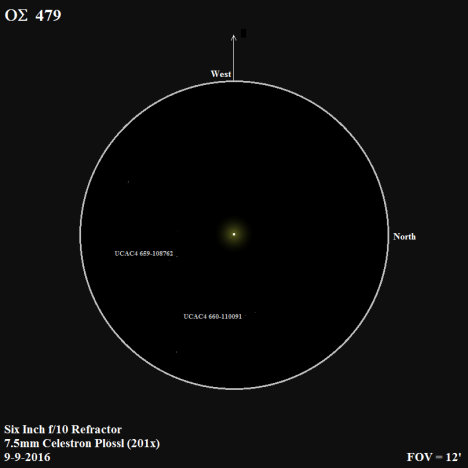

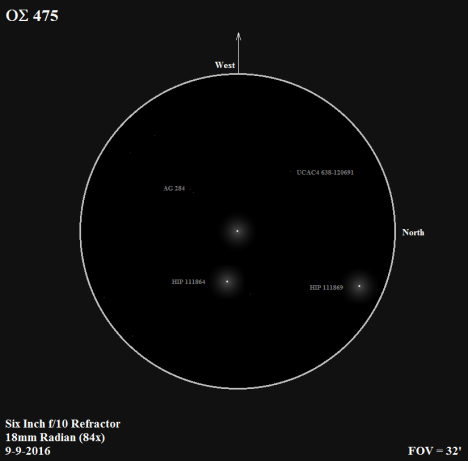

Continuing down the list of components for KR 60, “J” was added in 2012 in the form of the AJ and BJ components as HEL 4. The measures were made in 2009 with the 200 inch Hale Telescope on Mt. Palomar and the ten meter Keck II Telescope in Hawaii as part of a speckle binary survey led by K. G. Helminiak, thus the HEL prefix for the two components. The next component, “K”, was first discovered and measured in 2006, prior to the first measures of the “J” component. Added as HZE 5 AK, it was found during a survey for exo-planets which was led by A. N. Heinze and five other observers.

The remaining nine components, all in the range of 15th magnitude or slightly brighter, were first measured by Marcel Fay in 2012 and added into the WDS as FYM 118. The 1999 first dates of measure in the WDS were derived from data in the 2MASS and UCAC4 catalogs, as well as the AAVSO‘s APASS survey. Curious as to what prompted the addition of the nine faint stars, Fay replied in an email that he was interested in the possibility of shared proper motion between the cluster of stars in and around KR 60. Fay was replying to an email sent to him by Dr. Wilfried Knapp, who is the co-author of a more detailed study of KR 60 which the two of us did. That study has been published here in the Journal of Double Star Observers (JDSO). As to whether shared motion exists between the cluster of stars surrounding KR 60, we concluded “currently existing data does not give any serious hint in this direction — proper motion of most stars is according to UCAC5 very small with rather different PM vector direction and GAIA parallax data is currently not available.”

So as star dust settles over KR 60, we now have answers to why so many components were added to this system. “B” is the only star in the system which is a genuine binary companion, so it unquestionably belongs here. Based on statements by the various observers involved, we know the “C” through “I” components were added as reference points for tracking the high rate of proper motion of the AB pair, with the exception of “F”, which Barnard added to track the motion of “B” relative to “A”. Proper motion doesn’t seem to have played a role in the addition of the “J” and “K” components, but there is the suggestion of an orbital relation in regard to “J”. Shared common motion was the rationale for adding the “L” through “M” components. Whether that’s an adequate basis for the addition of a large group of faint stars as KR 60 components is at the very least an open question since at this point there is no clear indication that such motion exists. The preliminary work by Dr. Knapp and I failed to turn up any conspicuous evidence of shared motion, but what is really needed are distances for all these stars. Those aren’t available as of the date this is being written. Hopefully, when all the GAIA data is released in a few years, we’ll have parallaxes for each of these stars, which should provide a much clearer picture of where the FAY components lie in relation to each other in interstellar space.

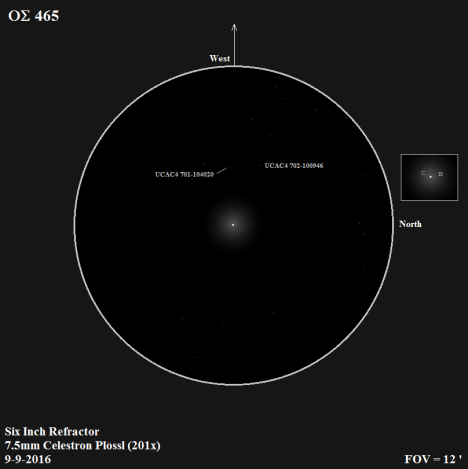

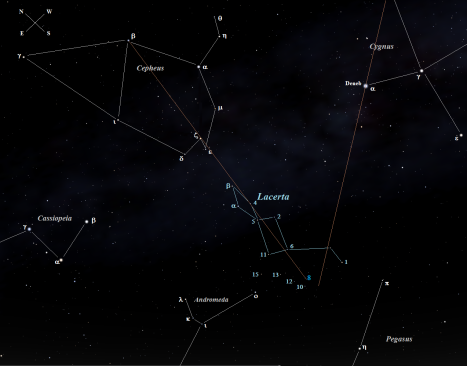

Filed under: 4. Choose a Constellation:, Cepheus | 6 Comments »